Where History Reigns

By DAVID BROOKS

Although as a child I had turtles named Disraeli and Gladstone, I was never invited to sip Champagne with the queen until yesterday. Although I’ve been an Anglophile all my life, I was never able to participate in a fawning orgy of Albion worship until the British ambassador’s party for the monarch yesterday afternoon.

It was wonderful.

I got to enjoy many of the features I love about Britain: repressed emotions, overarticulate conversationalists and crustless sandwiches. It reminded me why over the decades so many of my Jewish brethren have gone in for the “Think Yiddish, Act British” lifestyle — shopping at Ralph Lauren and giving their sons names that seem quintessentially English: Irving, Sidney, Norman and Milton. More deeply, it reminded me why Britain is such a successful country.

Britain is a nation with the soul of a historian. Its society is studded with institutions that keep the past alive, of which the monarchy is only the most famous. Its press is filled with commemorations, anniversaries and famously eloquent obituaries. Britain has always produced politically engaged celebrity historians, from Gibbon, Macaulay and Trevelyan down to Simon Schama, John Keegan, Andrew Roberts and Niall Ferguson today.

In short, Brits live with the constant presence of their ancestors. When Isaiah Berlin compared F.D.R. and Churchill, he observed that while Roosevelt had an untroubled faith in the future, Churchill’s “strongest sense is the sense of the past.”

History, in the British public culture, takes precedence over philosophy, psychology, sociology and economics. And with a few obvious exceptions, British historians have not seen history as the unfolding of abstract processes. They have not seen the human story as the march toward some culminating Idea.

Instead they’ve seen history as a hodgepodge of activity — as one damn thing after another. As a result, George Orwell generalized, the English “have a horror of abstract thought, they feel no need for any philosophy or systematic ‘worldview.’ ” This isn’t because they are practical — that’s a national myth, Orwell wrote — it’s just that given the stuttering realities of history, they find systems absurd.

Even philosophers in Britain tend to be skeptics, and emphasize how little we know or can know. Edmund Burke distrusted each individual’s stock of reason and put his faith in the accumulated wisdom of tradition. Adam Smith put his faith in the collective judgment of the market. Michael Oakeshott ridiculed rationalism. Berlin celebrated pluralism, arguing there is no single body of truth.

This skepticism permeates national life, for while the British can be socially deferential, they are rarely intellectually deferential. The French and the Germans might defer to their intellectuals, and the Arabs might defer to their clerics, but the British public is incapable. That’s why the British trade unions could take on the upper classes in their day, and why the Brits had an open debate about European unification. The British elites exerted enormous pressure in favor of union, but the tabloid readers didn’t care.

The Brits’ historical consciousness means that in moments of crisis they can all swing together and act as one. But in normal times, as Orwell also noted, “the gentleness of the English civilization is perhaps its most marked characteristic.” Americans talk of “happiness,” but Brits talk, less transcendentally, of “enjoyment.”

American journalists, for example, are spiritually descended from Walter Lippmann. We are always earnestly striving toward some future elevated state. British journalists are spiritually descended from Samuel Johnson. They are conversationalists enjoying the inevitable conflicts that, as W. C. Sellar and R. J. Yeatman put it, pit the wrong but romantic against the right but repugnant.

Before I slip totally into sceptred isle fanaticism, I should point out that it’s better to be an American Anglophile than to be British. As an American, you don’t actually have to put up with the snobbery, the cynicism and the insularity. You can choose the slice of Britain you want to admire.

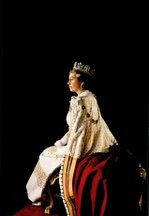

The slice I was enjoying yesterday on the ambassador’s lawn, as hundreds of Washington power broker types directed their rapturous attention toward Her Majesty, is the Britain that doesn’t often fall for ludicrous ideas. It’s the Britain that has revitalized its economy even while France struggles, and has mostly preserved the pillars, like the monarchy, of its distinct national identity. It’s the Britain still too well bred to mention, as a few expats and Yanks did yesterday, that the Queen looks a bit shorter than Helen Mirren.

The New York Times, May 8, 2007

4 comments:

Nicely put. Jeff

Err.. where is our skanky GG these days?

(real conservative)

"As an American...you can choose the slice of Britain you want to admire."

Never a truer word, laddie. Although the bits to ignore aren't snobbery, cynicism and insularity but the modern opposites which are frequently worse than what they replaced: inverse-snobbery, naive European-style Utopianism and rancid, second-hand internationalism.

Cato

That's the only thing that irks me about his fine piece. Everyone talks as if snobbery is some great social problem in the UK. I honestly wish people would get over it.

Post a Comment