The decline and fall of the Waspocracy

Beaverbrook was kind enough to point the way to this wonderful Kipling blog. I hope I am not going too far by republishing a large chunk of Publius' thoughts here, which unfortunately does not contain a referable permalink in and of itself (go over and scroll down the assorted links):

by Publius

The WASPs were the first modern culture. They discovered the secrets of a liberal democracy, an industrial economy and the habits and mores needed to develop and sustain both. They are also the first post-modern culture, the first to make as a matter of policy that habits and mores are not needed to maintain social and personal life. Perhaps they were needed once, the post-modernist might argue, as a kind of scaffold, but we have moved on, the edifice, now complete, is indestructible, so they assume. It would not be the first time a highly successful culture made the same fatal presumption. All societies have a margin of error, that cushion of economic and military strength that protects the society from collapse, driven by internal or external forces. Where the margin is slender, as in most societies, the tendency is for that culture to be risk averse. Where the margin is wider, the obverse.

Experimentation is not inherently bad, in fact it is essential for social and political evolution. The whole of English constitutional development was a series of experiments discarded, kept and improvised over centuries, Only in retrospect, generations and even centuries after the fact, were patterns discernible. Once these patterns became relatively clear statesmen and intellectuals began to talk about rights, liberties and the Constitution, though of course with their own agendas as context. The changes, reformations as Burke put it, were gradual and mostly political. The basic social compact on the level of local communities and families changed very little. It was here, at this basic level, that the margin of error was always smallest, until the industrial revolution.

The economic transformation Britain experienced during the late Georgian era, and then exported to the rest of the European world, to a greater or lesser extent, strained society to its limits. At first the change strengthened traditional family and gender mores and roles, as crisis often does. But over the longer term, perhaps as early as the mid-Victorian era, the traditional family was economically undermined. It was now practical for an adult individual, men at first but eventually women as well, to support themselves independently. The ability to earn a wage does not entail the ability to live life as an adult. What Slate identified as adult behaviour is a specifically WASP adult code of behaviour. It was an Anglo-Saxon solution to the day-to-day problems of modernity, of life as an autonomous individual away from traditional community. Other cultures, Continental and non-European posed their own solutions. Yet it was a definition of individual adulthood that was meant to lead back to a fairly traditional conception of family.

What is most instructive about the arc of the WASP code is how it collapsed, how the freedom granted by the industrial revolution allowed for ever more, and ever more radical, social experimentation. The margin of error of the modern world is unprecedented. We have spent now two generations engaged in a dramatic re-definition of family and the social role of the individual, both in the family and society. The demographic crisis that is now afflicting Europe, and slowly showing itself in North America, is the end result. Yet the interpretation to take away from the end of WASPness is not contempt for the modern Icaruses of the Left, though that is certainly important, but to view the process as social experimentation gone bad. There was nothing wrong with questioning the traditional family. Like any institution it requires questioning to prevent stagnation and irrelevancy, which applies just as much to traditional values, themselves products of previous questionings. The problem is how to manage social change.

Burke must be the starting point in this. His insights were political but they hold relevancy for social change as well. The key points are well enough known; gradual and organic change, reformation when necessary and revolution only as dire last resort. Methodologically his approach was empirical and skeptical of the abstract or the new. Yet this is ultimately an unsatisfying and incomplete approach. The abstract should be a guide to the practical; a bird's eyeview of the day-to-day. Theorizing should be a pyramid of ever wider generalizations, eventually crystallizing into principles. Modern epistemology eschews this approach as impossible, perhaps also undesirable. One camp, of which sadly Burke was a member, held that abstractions, beyond a certain point, are impossible. Even in Reflections on the Revolution in France, this approach hints toward one of its greatest dangers: relativism.

The accusation, especially toward Burke, seems absurd. Yet we see here and there in Reflections how he says that what worked in England may not work in France. At the face of it this seems only sensible. Different histories, different contexts and therefore different approaches. But where is the universalist call that was one of Thomas Paine's main themes in his reply to Reflections, the Rights of Man? Burke's defenders can easily say that Paine's work is a perfect case in point of the problems of using abstract theories to define political rights, or indeed anything; they become too abstract. The two works are symptomatic of this dualism in western political and social thought. One school rejects abstract theorizing as useless at best, at worst harmful. The other school rejects the practical school as too narrow, too particular and perhaps even too reactionary to provide profound answers to new problems. The dilemma of forest and trees and all that.

Perhaps, had the conservatives of the 1960s, not just political but social as well, provided constructive answers to the challenges of that era, something other than the old ways are the best, the nihilists wouldn't have won out. The New Left of the time was theory, without reference to facts, turning on itself. Take, again, the idea of cultural relativism. Burke might have wondered whether British institutions could work in France, he would have recoiled from the notion that the culture of primitive savages was morally and intellectually equivalent to his own. Yet that is the central tenet of multiculturalism, which is egalitarianism taken to an extreme without reference to life as actually lived by human beings on earth. The conservative might reply, at this point, that the 1960s were just the time when a frankly reactionary approach was necessary, anything else would have been compromise with nihilism. This is certainly a danger if one concedes the moral and intellectual high ground to the opposition, as the Old New Deal Left conceded to the New Left of the 1960s. A creative re-imagining, a questioning of old assumptions about family and society that recognizes its inherent importance, is not such a concession. Even today, especially over issues of family and marriage, there is a reactionary tendency among conservatives. This may seem like prudence but is it?

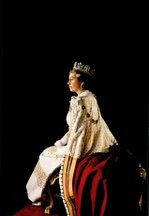

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

2 comments:

Yes, it's hard to link to his thoughtful work, so it's probably okay. I've had to do same on a couple of occasions.

I'm a long time fan of The Gods of the Copybook Headings. Some of the best editorial writing out there anywhere.

Burton

Post a Comment