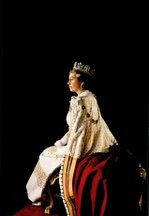

Vive La Reine!

History is far stranger than fiction, a truth demonstrated again this week with revelations that in 1956 Guy Mollet, the then French Prime Minister, proposed a union between Britain and France. The soul shrinks at such a prospect. The two best enemies in all the world under one government? Under Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II no less. Devouted Churchillians will know that the great man himself proposed such a union in the dying days of the Third Republic, as what remained of the French Army evaporated before the German advance. The proposal was Churchill at his most romantic and pragmatic. It would have allowed the French to maintain that they were never defeated by Nazism, a kind if misplaced gesture; it also would have granted Britain immediate and legal control - though for how long? - over the French fleet and colonies. In the end the British were forced to sink much of the French fleet in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir and to gradually pry the French colonies from the control of Vichy.

Mollet's eccentric gesture must be seen in the context of its time. According to recently discovered documents, the proposal was made on the eve of the joint Franco-British retaking of the Suez Canal from that cretin Nasser. Eden had shown signs, at least to the minds of some senior French officials, of vacillation. The proposal of union, even if sure to be rejected, being dramatic and unexpected might have made any backdown over Suez more awkward for the Cabinet and No. 10. "How can we betray so loyal an ally as France?" one might have heard a hesitant minister ask had the Cabinet gotten cold feet over the attack. It was the sort of off the wall, desperate and ruthlessly calculated thing that the Quai d'Orsay has specialized in for centuries.

More broadly than the Suez Crisis, which in the end brought down both Mollet and Eden, the first half of the twentieth century had been unkind to the two former rivals turned erstwhile friend, though especially so for France. The halting and incomplete process of industrialization left the country vulnerable to the rise of the Rhur-powered German economy. This combined with the socio-political divides highlighted over secularization, the Dreyfus Affair and in the 1930s the short-lived Popular Front government, gave the impression to the French people, and to the outside world, of a weak and divided nation. The strange defeat of 1940, in Marc Bloch's famous analysis, only confirmed the image of a weak and fading France. The Fourth Republic (1946-1958) proved another blow. Despite hopes that it would remedy the oft remarked upon instability and ineffectiveness - the latter perhaps exaggerated - of the Third, the disaster of Suez, a still struggling economy - as the Federal Republic of Germany boomed - and finally the Algerian crisis ensured its demise. In this context a desperate French leader might be willing to swallow some national pride for the sake of short-term advantage.

All this changed in 1958. Immediately after the Second World War France had rejected Charles de Gaulle's calls for strong, and at times frankly authoritarian leadership. In 1958 a large majority of the French public practically begged the old war leader to save them from themselves. So he did. Despite being a dirigiste of the old school, de Gaulle was a great improvement on the muddling socialists who dominated the politics of the Fourth Republic. Sweeping away internal trade barriers, protecting private property from the predations of the Left and Far Left and otherwise maintaining a positive climate for investment and trade, de Gaulle engineered an economic miracle almost as spectacular as that of Konrad Adenauer and Ludwig Erhard's Social Market next door. He also matched improved French economic prowess with a more belligerent foreign policy.

From the First Battle of the Marne until Suez the Anglo-French partnership had usually meant a more junior role for the Republic. It was Chamberlain who was the prime force at Munich, Bevin who lead the French toward NATO in 1949 and Eden who first proposed aggressive action against Nasser in 1956. De Gaulle replaced this deference, born out of internal social and economic weakness, with an often juvenile anti-anglo-saxonism. Rejecting Britain's entry into the Common Market twice, pulling out of the NATO command structure in 1966, the pompous declaration at Montreal City Hall in 1967 of "Vive le Quebec Libre," and frequent prickings of the Americans over Vietnam, were as much a matter of policy as of nationalistic revanche for the former leader of the Free French.

The Britain of Harold MacMillan and Harold Wilson, de Gaulle's contemporaries at No. 10, was a bleak place. Supermac had made it a point to suck up to Eisenhower (if you have a more polite description, that is still accurate, please propose it in the comments) and while both he and de Gaulle oversaw the dismantling of their respective global empires, it seemed far more like a retreat for Britain than for France. Wilson had come to power promising to modernize Britain in the "white heat of technology." Hopes that technocracy might overcome class, tradition and stagnation were ill-placed. After Wilson came Heath and then Wilson again and then Callaghan. Then there was the Winter of Discontent. Members of the House of Commons openly talked about Britain becoming another Portugal. If the France of Georges Pompidou, de Gaulle's apprentice and successor, did not prosper as before, it seemed far more vigorous during Stagflation than its old rival. Certainly no French President of the time was seen running to the IMF for help to prop up the franc.

Then came the Eighties. Britain went with Mrs Thatcher and France with Francois Mitterrand. Germany had begun to walk away from the Social Market with Willy Brandt's government. From the distance of a quarter century the three decades after 1945 seem an anomaly. Britain, the homeland of laissez-faire became a case study of the dangers of democratic socialism. Germany and France, previously contemptuous of the free market, made a short-lived truce and prospered greatly as a result. The old patterns re-asserted themselves twenty-five years ago. The French today speak deridingly of Anglo-Saxon capitalism, while straining to catch up to the Anglo-Saxon economies, as they did a century ago. German authoritarianism has assumed a new more pleasant, if bloated, welfare state form in the last years of the 20th century. The Franco-British Union was a dead letter for the simple reason that the two nations were culturally incompatible. One nation prided itself on being "the Mother of the Free," the other "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity." If those differences seemed obscure in 1956 they have become clearer again today. Tony Blair notwithstanding.

Publius

Originally posted at The Gods of the Copybook Headings

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

7 comments:

This is one of the greatest essays ever published at The Monarchist! It also beats hands down anything I've read on this story in the mainstream media. I'm truly in awe at the amount of thought packed into the paragraphs and the way it all flows so beautifully together. This is narrative history and national biography as it should be written, but most especially, you've put everything in its proper perspective for us (not easy to do) and drawn all the right lessons. Hats off!

Excellent piece! Welcome aboard, Kipling.

Tweedsmuir

I see that I was once again strung out on cafeine with my "greatest post ever" and "truly in awe" hyperventilation. Let me just say, using a more measured tone, that I have added this well written short essay under "treasured posts".

Publius:

de Gaulle's Anglophobia isn't some petulant teen reaction but comes from the sometimes shabby treatment he received from Roosevelt. FDR had no compunction to recognize the Vichy regime and deal with the regime or give support to Girard- a pétantist.

As for the Brits wrestling the French colonies from Vichy Really? I don't remember reading the Brits intervening in Chad nor did the former intervene to help the French garrisons in Indochina when the soldiers were massacared by the Japanese.

The Free French under Leclerc do also deserve some credit in redemming French honour from the débâcle.

True, France and Britian are incompatible on the surface but deeper down I do see more similarities than differneces.

In any case, the union never occured but it does provide an interesting footnote in the sometimes tumultous history between both countries

God shave the Queen!

Monarchist,

In any case I appreciate the kind words. Even without the cafeine.

Xavier,

FDR's shabby treatment of de Gaulle might explain the General's anti-Americanism but where does the anti-British and anti-Canadian sentiment come from? Churchill literally kept de Gaulle alive more than once. How does this explain the veto over Britain's entry into the Common Market?

"As for the Brits wrestling the French colonies from Vichy Really? I don't remember reading the Brits intervening in Chad nor did the former intervene to help the French garrisons in Indochina when the soldiers were massacared by the Japanese."

What about the liberation of Algeria and Tunisia (admitedly a joint Anglo-American operation)? What about the raids on Dakar? What realistically could the British have done in Indochine, given how quickly they lost Hong Kong and Singapore? How about the Free French and Vichy French battling for control of Syria? The British were financing and equiping the Free French there and elsewhere.

Moncharist:

I'll have to read de Gaulle's biography to find out where the deep seated anti British and Canadian sentiment came from.

As for the areas in the Mideast, the liberation was in British strategic interests- the Vichy navy was anchored in Algeria and the Brits (and Americans) wanted to get their hands on it since it would increase the Allied's striking power. Also the Allieds threatened the Axis' underbelly which they eventually attacked Provence and Italy via Sciliy

As for Syria, that was to prevent the Vichy from threatening Iraq

(and Jordan) or giving support to the golpistas in the former. We all know how Churchill was legitmatiately frighetned had Rashid's(?)coup succeded and the Germans had a modicum of strategic acumen.

You're right that the Brits and Americans supplied the French. The French simply couldn't do anything on their own as of 1940

Post a Comment