Bring Back the Bill of Rights

"The Crown has become the mysterious link, may I say the magic link, which unites our loosely bound but strongly interwoven Commonwealth of Nations, states and races. People who would never tolerate the assertions of a written Constitution which implies any diminution of their independence are the foremost to be proud of their loyalty to the Crown."

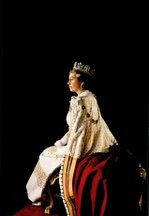

- Sir Winston Spencer Churchill  Her Majesty gives Royal Assent to the Constitution on April 17, 1982, paving the way for independent Trudeaupia, a Napoleonic Charter and, as William Gairdner writes, a Canada deprived of its noble historical roots. Happy 25th.

Her Majesty gives Royal Assent to the Constitution on April 17, 1982, paving the way for independent Trudeaupia, a Napoleonic Charter and, as William Gairdner writes, a Canada deprived of its noble historical roots. Happy 25th.

Chastising the Charter by William Gairdner

We have been treated of late to a variety of opinions published in the National Post concerning Canada’s 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which is now 25 years old. For this reader, however, the real story of the Charter and its damaging consequence for our mutual life was left out.

When it is told by future historians, I think it will go something like this. Prior to the founding of Canada under the British North America Act of 1867, all those in the British colonies of the New World lived under English parliamentary law and their court proceedings were judged according to common-law precedent. Law made by parliamentarians was the highest law of the land. But even before deciding on new statutes, English parliamentarians would usually make passionate appeal to common law because in the public mind such precedents were considered a precious historical inheritance from what G.K. Chesterton called “the democracy of the dead.” Which is to say, a priceless gift of moral and legislative wisdom from our ancestors, near and far.

In the rising democratic spirit of the times, however, these Canadians-to-be once or twice revolted against British rule to achieve what they called “responsible government.” By this revolutionary slogan they meant they wanted those who made their laws to answer to them, the people. They were finished with colonial governors bossing them around who were responsible only to the English Parliament in London, or to the Privy Council some 6,000 miles away, for neither entity had any obligation to answer to those over whom they ruled. The BNA Act of 1867 changed all that, and Canada finally got responsible government. The new Canadians would now grow their own British-style parliamentary tradition and common-law inheritance (with the exception of Quebec, which would use French Code law in addition), and would at last have political masters responsible to them alone. They would at last be able to hire and fire their own law-makers.

This hopeful regime lasted a mere 115 years until 1982, when Prime Minister Trudeau got the Charter he wanted. Now among the things Trudeau had always mocked and despised were English concepts of governance such as Common Law. He was very much unsettled by the idea of ten provincial legislatures all making their own sovereign laws, sometimes in conflict with each other. Of course, that right of sovereign lawmaking by local citizens was a mark of the glory and freedom of the English system. But to a francophone intellectual the very idea of a nation without a unitary Napoleonic-style Code hovering over it which, like a magnet under the tablecloth would orient all political and moral iron filings, was abhorrent. In short, Trudeau despised any system under which “the people” in Parliament (and in each provincial legislature) had the unfettered right to create the highest law of the land. This complaint is typical of anyone raised in the Cartesian intellectual tradition, where rational conclusions are supposed to flow from fixed axioms, and laws must follow clear and distinct principles, rather than emerge from potentially conflicting precedents. That means that laws must be shaped by a higher Code, and to hell with the common-law insights of ancestors. What did they know about modern socialist theory, anyway? Nothing of course. So forget them, was the feeling. What Trudeau wanted, and got, was a new, abstractly-worded Code law to be imposed upon the freedom of legislators in Canada’s Parliament, all provincial legislatures, and courts. The meaning of all the articles of his Charter, if challenged, would be decided by unelected judges who were above the democratic political fray and – here is the rub – who would never be responsible to the people! This meant that from henceforth the Canadian people were once again to have the spirit of their most important laws and moral traditions decided by people they did not place in power, and whom they would never be able to remove. At one stroke, Canadians were returned to the political condition they suffered under prior to 1867. Morally and legally speaking, Canadians have become colonized again, and this time, not by a foreign power but by their own hand.

This was a radical and deeply wrenching re-orientation of Canada’s entire judicial and political tradition muscled into position by one man who was drawing from a tradition inimical to the English way of life. He was not citing Magna Carta, or Locke, or Blackstone or Burke as his intellectual teachers. No. He repudiated the glories of the English tradition, and embraced instead the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the teacher of Marat, Robespierre and Danton – radical intellectuals, socialists, and murderers all – hinting blithely as he did so of Rousseau’s concept of “the General Will” - called in French, La volonté générale. In one of Trudeau’s last publications, Pierre Trudeau Speaks Out On Meech Lake, he used that phrase repeatedly (and largely inaccurately, for I don’t believe he ever really understood it). For example, on page 45 he urges Canada to create “a national will … une volonté générale as Rousseau had called it.” He did not realize that a national will is something subtly different from Rousseau’s idea of a General Will. The former may be properly thrashed out in the heat of debate and passed by a majority, with disagreements tolerated. But the latter is a totalizing concept declared by edict of the supreme ruler (and Rousseau advocated the death penalty for all who opposed it once it was decided). Nevertheless, this was but one of Trudeau’s many references to Rousseau as his personal intellectual and moral authority. I do not hesitate to say that Rousseau’s whole notion of the General Will was - and it remains – a Franco-european conception of unitary national governance alien to the British way of life and to our inherited political history since Magna Carta, if not (as many would argue) a precursor to much more sinister conceptions of governance such as nearly ended European civilization in the 20th century.

In this way, Canada has been changed, uprooted, altered beyond recognition from its noble historical roots. This is the real significance of the Charter.

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

9 comments:

It was the beginning of the end of what was the greatest country in the world... oh woe is me..

(real conservative)

Beautifully written and deeply insightful.

(http://dominionpages.blogspot.com)

That so few recognize the potential for tyranny in granting to 9 unaccountable elites the power to rule the country (read McLachlin's ideas on judicial prerogatives)is indeed disturbing. We now live or die by the 9 sombre Santas.

Burton

The Charter means sweet nothing to me personally. I have never been one to wake up in the morning and think: thank God for the Charter. It has mostly been seen and used by those with a particular agenda as a tool to advance their special - many times, controversial - cause by circumventing the democratic channels. I have on the other hand been quite thankful for the Notwithstanding Clause, which means that Parliament still has the last say if a cabal of judges ever does something totally damaging to individual liberty or truly contemptible against the people's interest. How anyone would want to do away with it, and place their unfettered faith in 9 unelected elites is just beyond me.

Of course, Parliament could also do something deeply damaging to individual liberty and majority interest, but at least it's easier to throw the bums out. Changing the Consitution, even in an emergency, I submit, could be extremely difficult, which is as it should be, if there was struck a better balance between the power of the courts and Parliament. But that's what happens when we look up to magistrates in awe and Parliamentarians in disgust. Perhaps that's why an apathetic people are more comfortable with the balance as it is tilted.

Let's bring on the euthanasia booths and shop you lot off to your final destinations so the rest of us can be spared your anguished obsessions over how other people live their lives; things that aren't any of your business and never have been.

So just to review:

The Constitution of my country is none of my business;

How my country is ruled is none of my business;

Your anguished obsession over how we put our freedom of speech to use is hunky dory;

You would like to murder those who disagree with you.

Have I missed anything?

Perhaps in the future you could spare yourself much trouble by simply not visiting this site, you anencephalic wanker.

Burton

Don't worry. That won't be hard to do.

Up the Queen!

God shave the queen

Post a Comment