Men and Principles - Part Two

Tamworth

Tamworth

The death of George IV in 1830 lead to the traditional dissolution of the House and a general election. Wellington, who had served as Prime Minister since 1828, was able to govern for a few months afterwards but lost a vote of confidence on the issue of parliamentary reform in November. Within a year the nation was gripped by the worst constitutional crisis in its history. The new Whig Prime Minister, the 2nd Earl Grey, introduced a reform bill that proposed to do away with most of the country's rotten boroughs, dramatically expand the size of the electorate and grant seats to cities like Birmingham and Manchester. The Tories responded violently and the new monarch, William IV, was adamantly opposed to the bill. The Commons had rejected a first bill in 1831 but passed a second version by a hundred votes. The Tory dominated Lords, despite overwhelming and extremely vocal public support for reform, threw out the second bill, provoking a constitutional crisis. A third bill introduced by the Whig ministry in early 1832 was subject to an attempt by the Tories to gut it through amendments in committee.

Frustrated Grey, with the unanimous support of Cabinet, went to the King to ask for the creation of new peers to swamp the Lord with members sympathetic to the bill. The King resisted such a drastic move, Grey and the Cabinet resigned and Wellington was recalled but failed to form a government. Riots ensued and fears of revolution became widespread. At last the King himself defused the crisis by making quiet threats to the peers, in an unpublished letter, that he would acede to the Whig demands if opposition to the latest bill did not cease. The bill passed with Wellington securing passage by convincing many to abstain from the vote. When the new reformed parliament met Wellington is suppose to have said, "I never saw so many shocking bad hats in my life."

Catholic Emacipation and Parliamentary reform were now a fact, and Sir Robert Peel, who succeeded Wellington as leader of the Tories, made a cold and hard headed political calculation - if the Tories continued to oppose the fait accompli of reform they doomed themselves not only to political irrelevancy but to possible annihilation as well. Shortly after his appointment as Prime Minister in 1834 he published what became known as the Tamworth Manifesto, widely regarded as the founding charter of the Conservative Party, its highlights were:

Peel accepted that the Reform Act of 1832 was "a final and irrevocable settlement of a great constitutional question". He promised that the Conservatives would undertake a "careful review of institutions, civil and ecclesiastical". Where there was a case for change, he promised "the correction of proved abuses and the redress of real grievances". Peel offered to look at the question of church reform in order to preserve the "true interests of the Established religion". Peel's basic message, therefore, was that the Conservatives "would reform to survive".

The new Conservatives were to lose the subsequent election but remained a viable party and steadily grew in strength until regaining power in 1841, with Sir Robert Peel at the helm. What Tamworth hadn't been able to do was effect a lasting reconciliation between the party's industrial and agarian factions. The Corn Laws, an issue pushed to the political periphery by the great controversies over Catholic Emacipation, parliamentary reform and the abolition of slavery (1834), remained dormant under Lord Melborne's Whig administration (1835-1841) who refused to even touch the issue. On returning to power in 1841 Peel began a rapid program of tariff reduction, targeting virtually every commodity, except for those covered by the Corn Laws (wheat and barley), even going so far as re-introducing the income tax, a war-time measured originally introduced in 1797, to make up for the fiscal shortfall. Whatever Peel's personal views on the Corn Laws for most of second ministry they remainded carefully guarded. A weak harvest in 1844, the first reports of a potato blight in Ireland in late 1845 and a new political movement would force Peel's hand.

Mr. Cobden and Mr. Bright

Weak harvests were nothing new in British history, what changed in the 1840s was the emergence of a mass political movement in favour of free trade. Using the Anti-Slavery movement as a model, the Anti-Corn Law League, founded in 1836 and reconstituted two years later, waged a national campaign to abolish the Corn Laws. A self-made businessman and autodidact of extraordinary breadth, Richard Cobden became convinced of the need for free trade as a way of easing the lot of the British poor. Along with a brilliant young orator, also from an commerical background, John Bright, Cobden became a leader of the Anti-Corn Law League. Speaking tours, letters to the editor, articles, pamphlets and winning seats in the House of Commons were all part of the League's strategy to gain repeal. In 1841 Cobden was elected to the House and spent the next five years becoming a professional nuisance to Peel and the Conservative ministry.

An 1843 speech in the House, blaming Peel personally for the suffering of the British poor, provoked a severe backlash against Cobden from the Conservative benches. Peel's own tariff cutting, successive and increasingly bad harvests in the 1840s and the growing influence of the Anti-Corn Law League, were rapidly narrowing the Prime Minister's field for maneuver. Confirming the suspecions of many backbenchers within his own party, he reacted to the first reports of the Irish Potato Famine by calling for a gradual reduction in the corn tariff to the nominal rate of one shilling per bushel in three years. What had been a simmering dispute within the Conservative caucus became a revolt. An announcement in the Times in early December 1845 that the government would begin the process of repealing the Corn Laws early in the new year, sparked a series of ministerial resignations culminating with Peel's own.

The Queen called for the Whig leader, Lord John Russell, to form a government but he failed within a few days. Peel was recalled and introduced the repeal bill in Janauary. For the next six months Tories, Whigs and Radicals waged one of the most dramatic battles in parliamentary history. As in 1832 some talked of revolution; reports of famine in Ireland providing, depending on one's perspective, either a rationale or a pretext for Peel's persistence in pursuing abolition. In the ensuing political battle two minor players in parliamentary life entered the spotlight in early 1846, beginning brilliant political careers and a life long animosity and rivalry.

The Lion and The Unicorn

In Richard Aldous' recent examination of the relationship between William Ewart Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli, he drew upon Lewis Carol's Alice Through the Looking Glass for literary allusion. In the Carol story a lion and a unicorn are seen fighting over a crown in a never ending and very noisy battle. Lewis was not so subtly mocking Gladstone, the lion, and Disraeli, the unicorn. The beginning of that epic rivalry, that was to last until Disraeli's death in 1881, was in many ways those six crucial months in 1846. Many of Peel's artistocratic and gentry supporters had gone into active opposition, lead by the young firebrand Disraeli. For support he now often turned to his most able minister, the Colonial Secretary William Gladstone.

In his mid-30s at the time Gladstone came from a wealthy family of Liverpool merchants, little different in origins from that of Sir Robert Peel, though his family was less successful. Entering Parliament more than a decade earlier as an ultra-Tory, he had been opposed to Catholic Emancipation, parliamentary reform and supportive of the Corn Laws and even slavery, which he argued was a largely benevolent institution. Impressed by the young man's energy, administrative talent and oratorical brilliance, Peel had quietly begun advancing his career. Fearing religious controversy Peel placed the fiercely Anglican Gladstone in the Board of Trade, exposing the Classics and Mathematics graduate to economic issues. In his four years as Vice-President and then President of the Board, Gladstone began to drop his ultra-Tory assumption, becoming a passionate believer in free trade. In the battles of 1846 the young minister's firm grasp of trade issues provided an invaluable asset to Peel. Along with Richard Cobden, whom Peel would eventually credit with having done the most to bring about repeal, the three formed the nucleus of the pro-repeal forces in the Commons.

Disraeli, once an admirer of Peel, was appalled by the Prime Minister's volte face on the Corn Laws. Never much for statistics - which he famously dimissed with his throw away line, "lies, damn lies and statistics" - or tight logical reasoning or even careful empirical observation, Dizzy, as his friends and enemies were fond of calling him, used wit and style to attack and destroy Peel. At times he would stoop to conquer, citing some of Peel's old arguments in favour of keeping the Corn Laws against the Prime Minister, but Dizzy's essential strategy lay in rallying the backbenchers to revolt. Implying treachery, warning of agarian ruin and social anarchy, one of British history's greatest political actor delivered a superb performance. The division between protectionists and free traders, paralleling closely, if not perfectly, the divisions between the Conservatives' agarian and industrial electoral bases, might very well have finished the Peelite Conservative Party in any case. Nevetheless Disraeli had gone against his leader, whom he famous dubbed the "Arch-Traitor, and had made sure that any potential reppraochment would be impossible

"no longer leavened by a sense of injustice"

Wellington was fond of saying that he believed in men, not principles. It would be his great faith in the character and talents of Sir Robert Peel that would overcome his reservations about repeal. Uninterested in economics and of course a soldier by profession, the arguments of Ricardo and Smith were only so much air in the firmament for the Duke. HIs famous call to his fellow Tory peers of "right-about face," secured a smooth passage of the bill to repeal the Corn Laws through the upper house. That very night, June 25th, 1846, Peel's government was defeated on a matter of confidence, ironically a bill authorizing sweeping power for the government in dealing with the growing Irish crisis. His former backbenchers, the Whigs and the Radicals combined to drive Peel from office. Before the end he gave credit where it was due:

Sir, the name which ought to be, and which will be associated with the success of these measures is the name of a man who, acting, I believe, from pure and disinterested motives, has advocated their cause with untiring energy, and by appeals to reason, expressed by an eloquence, the more to be admired because it was unaffected and unadorned—the name which ought to be and will be associated with the success of these measures is the name of Richard Cobden. Without scruple, Sir, I attribute the success of these measures to him.

He concluded:

In relinquishing power, I shall leave a name, severely censured I fear by many who, on public grounds, deeply regret the severance of party ties — deeply regret that severance, not from interested or personal motives, but from the firm conviction that fidelity to party engagements-the existence and maintenance of a great party-constitutes a powerful instrument of government: I shall surrender power severely censured also, by others who, from no interested motive, adhere to the principle of protection, considering the maintenance of it to be essential to the welfare and interests of the country: I shall leave a name execrated by every monopolist who, from less honourable motives, clamours for protection because it conduces to his own individual benefit; but it may be that I shall leave a name sometimes remembered with expressions of good will in the abodes of those whose lot it is to labour, and to earn their daily bread by the sweat of their brow, when they shall recruit their exhausted strength with abundant and untaxed food, the sweeter because it is no longer leavened by a sense of injustice.

Losing his prominence and entering into semi-retirement Peel would live long enough to see the repeal take full effect in 1850. That year, while riding up Constitution HIll in London he was thrown from his horse, dying from internal injuries a few days later. Those Conservatives that remained loyal to Peel in 1846 became known as the Peelites, numbering between 50 and 70 MPs well into the 1850s, when they were gradually absorbed into the Whigs. Gladstone, who eventually assumed the leadership of the Peelites, refused to join the Whigs until the creation of the LIberal Party in 1859. Gladstone himself served two brilliant terms as Chancellor of the Exchequer and four terms as Prime Minister (1868-1874, 1880-1885, 1886, 1892-1894). His great rival, Benjamin Disraeli served two terms as Prime Minister (1868, 1874-1880), displaying the same oratorical flare and passion he showed in helping to destroy Peel's second ministry. As a practical politician, however, Dizzy switched to supporting free trade in the late 1840s once it was clear the policy was now widely popular.

The half century after Peel's death saw a steady decline in the price of grain, which began to plunge in the 1870s after technical advances in shipping reduced the "natural tariff" of distance. Economic historians tend to regard the repeal of the Corn Laws as the centerpiece of late Victorian economic prosperity, compelling Britain to re-orient its economy increasingly toward manufacturing, where it held a strong comparative advantage, and away from agricultural production. By the end of the century nearly half of British grain consumption came from overseas.

Cross posted at The Gods of the Copybook Headings

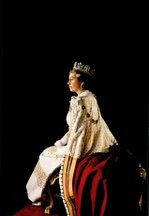

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

3 comments:

This is culturally-focused scholarship. No matter how many times I read through that political era, it's always a pleasure to refresh my knowledge of it.

And once Great Britain lost its comparative advantage, Free-Trade became the very policy that greatly contributed to her relative (to Germany and the USA) impoverishment - which then contributed mightily to the weakening of the Imperial Bond.

Empire Free-Trade at an earlier stage, might have been the ticket.

Kipling wrote (in part one ...):

"The hysterical reaction of the Canadian left to Free Trade with the US in the 1980s is a case in point. These patriots thought so little of Canada as a nation that simply because we would be buying more American goods, and have a few more of our companies owned by Americans, we would cease to be Canadian. Canada is a lot tougher than that."

And yet, we are - 20 odd years later - a weaker nation, whilst perhaps being a more affluent one.

Consider the decline of support for the Monarchy and the traditional institutions of Canadian nationhood over the last generation ...

perhaps our fuller integtation into American culture - via increased trade - has something to do with this.

Capitalism may be machinery, but even machinery needs to be retrofitted and repaired from time to time in order for it to work optimally and more efficiently.

But we must guard ourselves from letting the machinery become the system. The equipment is only a tool, and not our social and civic entirety.

Get my point?

Post a Comment