Monarchy is the key to our liberty

The institutions that attract the keenest scorn are actually what protect our democracy today

John Gray

Sunday July 29, 2007

The Observer (Be sure to click to the story to read the comments) It has become part of the liberal creed that monarchy and empire are anachronisms. The first embodies the hereditary principle, which no modern thinker can accept as a legitimate basis of government, while the second represents something still worse - the subjugation of peoples who should govern themselves. In future, the world will be organised into self-determining republics where all citizens enjoy equal rights. When empires are no more and kings and queens have been retired from service there will be enduring peace, and freedom will for the first time be universal.

It has become part of the liberal creed that monarchy and empire are anachronisms. The first embodies the hereditary principle, which no modern thinker can accept as a legitimate basis of government, while the second represents something still worse - the subjugation of peoples who should govern themselves. In future, the world will be organised into self-determining republics where all citizens enjoy equal rights. When empires are no more and kings and queens have been retired from service there will be enduring peace, and freedom will for the first time be universal.

This fable has a certain innocent charm. It turns the ironies of history into a simple morality play, and in a time that demands emotional uplift before anything else it has a powerful appeal. Yet this liberal narrative involves a massive simplification of events, and the ideal of self-determination it articulates has proved dangerous in practice. The grisly fiasco that continues to unfold in Iraq comes partly from the fact that none of those who engineered the war bothered to inquire whether the state Saddam ruled could survive a sudden injection of democracy.

Like most other states in the region, Iraq is - or rather it was, since for most practical purposes it no longer exists - a colonial construction. Cobbled up from provinces of the Ottoman empire by the British in the aftermath of the First World War it incorporated a number of distinct communities, none of which had ever been self-governing. The state of Iraq was not established peacefully - it was the British who, in the conflicts that preceded its foundation, began the practice of razing villages from the air - and it was always repressive. Yet as long as it existed it staved off a war of all against all among its component communities of the kind that has now been created.

As its colonial architects knew, the state of Iraq could not be democratic - the majority Shia population was bound to reject Sunni rule and the Kurdish minority would secede as soon as a democratic government was in place. Democracy in Iraq always meant the break-up of the state, and this has been the predictable result of regime change. But the impact of the US invasion goes far beyond the violence that prevails throughout the country. Iraq's neighbours are being sucked into the conflict and a regional war is not far off. By destroying Iraq the Bush administration has given a fatal nudge to post-colonial states throughout the region - and beyond.

How a larger war might develop cannot be foreseen, but a Turkish incursion into Iraqi Kurdistan is a growing possibility and the standoff between America and Iran could easily spiral out of control. Any such escalation would have repercussions in other zones of conflict - not least Afghanistan, where Nato forces could face strategic defeat of the kind that already faces US forces in Iraq, with dangerous knock-on effects in Pakistan. The result of destroying Saddam's Iraq has been to trigger a revolutionary unsettlement in the region whose global repercussions no one can foresee.

One thing we can know for sure. This is not the first time the attempt to reshape a post-imperial region on a liberal model has had horrendous consequences. Woodrow Wilson imagined that by promoting self-determination in eastern and central Europe after the fall of the Hapsburg empire the result would be civic nation-states. Instead it was ethnic nationalism based on hatred of internal minorities and decades of war and dictatorship.

The Bush administration's intervention in Iraq was hardly driven by Wilsonian idealism - but the hopes that inspire it are just as delusive as Wilson's. If ethnic nationalism was the beneficiary of self-determination in central Europe after 1918, radical Islam is the beneficiary today. In the Islamist 'new Middle East' that is being born as a result of misguided American intervention, women, gays and religious minorities will be oppressed in ways a post-colonial despot like Saddam never imagined.

Liberal opinion clings to the ideal of self-determination as an article of faith, but the truth is that constructing nation-states is nearly always a bloody business. The US became a modern nation-state only after a savage civil war, and France only after Napoleon. China is pursuing a similar path today - with consequences that in Tibet are not far from genocide. Nation building is a prototypical modern project, and yet the result has often been to undermine modern values of personal freedom and cosmopolitanism.

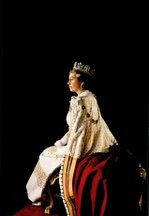

Look at those successful countries with borders that enclose different 'nations': Spain with its Catalans; the United Kingdom with Scots, English, Welsh and Northern Irish; Canada with the Quebecois. It is worth pondering the fact that the few genuinely multi-national democracies that exist today are mostly monarchies and relics of empire. Except in these irrational relics, democracy has nowhere managed to flourish at a multi-national level. Multi-national democracy has been most enduringly embodied in pre-modern constitutions.

Happily, we do not face in Britain any of the horrors that have accompanied the building of nation-states in other parts of the world. Still, it would be unwise to take our good fortune too much for granted. The monarchical constitution we have today - a mix of antique survivals and postmodern soap opera - may be absurd, but it enables a diverse society to rub along without too much friction.

Devolution to Scotland and Wales and the peace process in Northern Ireland have not, as doomsayers predicted, led to the British imperial makeshift collapsing. Instead they have probably strengthened it. Liberals tend to regard being subjects of the Queen as an insult to their dignity. But at least the archaic structures by which we are ruled do not force us to define ourselves by blood, soil or faith, and we are protected from the poisonous politics of identity.

Gordon Brown has committed himself to modernising the constitution, and there will be many who hope that he introduces a written constitution. As Iraq has demonstrated, however, reconstructing government on an abstract model has rarely been a reliable way of protecting liberal values. Let us hope the Prime Minister reflects on history, and confines himself to improving the workings of the ramshackle but curiously liberal framework we have inherited.

John Gray is professor of European thought at LSE, and author of Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the death of Utopia, published by Allen Lane.

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

4 comments:

I agree that in a freakish situation that represents a clear and present danger, where a totalitarian-minded PM were ever to accede to power, the monarchy and the constitution stand as bulwarks, and could be deployed efficiently and popularly to great effect. But I think that it is far more likely that liberties would be encroached upon incrementally, and I am no longer convinced that our Sovereign would be willing, nor think it politically feasible, to use her reserve powers in any meaningful, forthright way. In any event, I'm more concerned about the erosion of our liberties by an unelected judiciary - not by politicians who can be thrown out - and I'm not really sure about monarchy's reserve powers when it comes to unjust edicts handed down by the courts.

"Iraq's neighbours are being sucked into the conflict."

Remarkable, these verbal sleights-of-hand which anti-Americans use. In this case, the off-hand, almost casual implication that Iran and Syria, and their proxies Hizbollah and the rest, are extremely reluctant to get involved in the Iraqi insurgency and are being dragged in against their will... as opposed to saying to themselves, "what ho, here's an opportunity to really make a mess of those Americans' plans, and extend our own influence while we're at it." Bah.

Cato.

"Beaverbrook" writes:

not by politicians who can be thrown out

With all due respect "Lord Beaverbrook," I think we should be frank enough to say that this concept of democracy letting "us" remove bad politicians as a protection against vanishing liberty is little more than a grand hoax.

After all, it is the popular majority who can throw politicians out -- at least in theory. In practice, those at the helm among the electorate may differ more or less from the popular majority.

Remember that Abraham Lincoln was reelected.

Remember also how the size and reach of government has grown -- and liberty has yielded -- since the Guns of August were unleashed upon our civilization. The fact that politicians could be removed does not seem to have helped much against this.

I do, however, basically agree with "Beaverbrook" on the use of "reserve powers" vis-à-vis politicians.

I agree on the necessity of having the Crown retain real power over its reserve powers for the sake of protecting the electorate from the will of malicious politicians, should we ever find their hands on the levers of power.

That said, I am uncomfortable with the majority of this column's content. As a supporter of the Iraq War, I do not believe this conflict to have been an exercise in naivety. Whilst I have serious objections to the war's prosecution - especially the nation-building processes - I do not accept the thesis that certain peoples are incapable of governing themselves; with firm guidance, and over time.

But that's just it: achieving the kind of stability that the nations of the Crown Commonwealth enjoy takes a great deal of time. The British didn't make a habit of pulling out when things got bad. I don't mean to sound ham-handed here, but American military presence in Iraq, historically speaking, has been extraordinarily benign, well-intentioned and brief. Let's not forget that.

Post a Comment