The Burke of Our Times

ROGER SCRUTON, conservatism's great heavythink and the English-speaking nations' most pre-eminent Burkean, is (to copy the Gods of the Copybook Headings), "one of the most perceptive critics of the modern world. A professional philosopher, Scruton's insights have a holistic depth so sorely lacking in much of the professional punditry. Unlike most academics...his writing is striking by being not merely intelligible, a feat for anyone who has emerged from extensive contact with academic philosophy, but elegant". There is an abundance of highly recommended reading to choose from, but a useful starting point would be his 2003's Why I became a conservative over at The New Criterion. Here are some selected quotations (headings by me) from one of conservatism's "Great Contemporaries":

ROGER SCRUTON, conservatism's great heavythink and the English-speaking nations' most pre-eminent Burkean, is (to copy the Gods of the Copybook Headings), "one of the most perceptive critics of the modern world. A professional philosopher, Scruton's insights have a holistic depth so sorely lacking in much of the professional punditry. Unlike most academics...his writing is striking by being not merely intelligible, a feat for anyone who has emerged from extensive contact with academic philosophy, but elegant". There is an abundance of highly recommended reading to choose from, but a useful starting point would be his 2003's Why I became a conservative over at The New Criterion. Here are some selected quotations (headings by me) from one of conservatism's "Great Contemporaries":

A nation is defined by its culture

The Old Fascist was de Gaulle, whose Mémoires de guerre I had been reading that day. The Mémoires begin with a striking sentence—“Toute ma vie, je me suis fait une certaine idée de la France”—a sentence so alike in its rhythm and so contrary in its direction to that equally striking sentence which begins A la recherche du temps perdu: “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” How amazing it had been, to discover a politician who begins his self-vindication by suggesting something—and something so deeply hidden behind the bold mask of his words! I had been equally struck by the description of the state funeral for Valéry—de Gaulle’s first public gesture on liberating Paris—since it too suggested priorities unimaginable in an English politician. The image of the cortège, as it took its way to the cathedral of Notre Dame, the proud general first among the mourners, and here and there a German sniper still looking down from the rooftops, had made a vivid impression on me. I irresistibly compared the two bird’s-eye views of Paris, that of the sniper, and my own on to the riots in the quartier latin. They were related as yes and no, the affirmation and denial of a national idea. According to the Gaullist vision, a nation is defined not by institutions or borders but by language, religion, and high culture; in times of turmoil and conquest it is those spiritual things that must be protected and reaffirmed. The funeral for Valéry followed naturally from this way of seeing things. And I associated the France of de Gaulle with Valéry’s Cimetière marin—that haunting invocation of the dead which conveyed to me, much more profoundly than any politician’s words or gestures, the true meaning of a national idea.

{...}

No such thing as moral or spiritual progress

When I first read Burke’s account of the French Revolution I was inclined to accept, since I knew no other, the liberal humanist view of the Revolution as a triumph of freedom over oppression, a liberation of a people from the yoke of absolute power. Although there were excesses—and no honest historian had ever denied this—the official humanist view was that they should be seen in retrospect as the birth-pangs of a new order, which would offer a model of popular sovereignty to the world. I therefore assumed that Burke’s early doubts—expressed, remember, when the Revolution was in its very first infancy, and the King had not yet been executed nor the Terror begun—were simply alarmist reactions to an ill-understood event. What interested me in the Reflections was the positive political philosophy, distinguished from all the leftist literature that was currently à la mode, by its absolute concretion, and its close reading of the human psyche in its ordinary and unexalted forms. Burke was not writing about sociaism, but about revolution. Nevertheless he persuaded me that the utopian promises of socialism go hand in hand with a wholly abstract vision of the human mind—a geometrical version of our mental processes which has only the vaguest relation to the thoughts and feelings by which real human beings live. He persuaded me that societies are not and cannot be organized according to a plan or a goal, that there is no direction to history, and no such thing as moral or spiritual progress.

{...}

To organise society around rational pursuits is irrational

Most of all he emphasized that the new forms of politics, which hope to organize society around the rational pursuit of liberty, equality, fraternity, or their modernist equivalents, are actually forms of militant irrationality. There is no way in which people can collectively pursue liberty, equality, and fraternity, not only because those things are lamentably underdescribed and merely abstractly defined, but also because collective reason doesn’t work that way. People reason collectively towards a common goal only in times of emergency—when there is a threat to be vanquished, or a conquest to be achieved. Even then, they need organization, hierarchy, and a structure of command if they are to pursue their goal effectively. Nevertheless, a form of collective rationality does emerge in these cases, and its popular name is war.

{...}

All you need is love

Moreover—and here is the corollary that came home to me with a shock of recognition—any attempt to organize society according to this kind of rationality would involve exactly the same conditions: the declaration of war against some real or imagined enemy. Hence the strident and militant language of the socialist literature—the hate-filled, purpose-filled, bourgeois-baiting prose, one example of which had been offered to me in 1968, as the final vindication of the violence beneath my attic window, but other examples of which, starting with the Communist Manifesto, were the basic diet of political studies in my university. The literature of left-wing political science is a literature of conflict, in which the main variables are those identified by Lenin: “Kto? Kogo?”—“Who? Whom?” The opening sentence of de Gaulle’s memoirs is framed in the language of love, about an object of love—and I had spontaneously resonated to this in the years of the student “struggle.” De Gaulle’s allusion to Proust is to a masterly evocation of maternal love, and to a dim premonition of its loss.

{...}

Liberty equals respect for traditional authority In effect Burke was upholding the old view of man in society, as subject of a sovereign, against the new view of him, as citizen of a state. And what struck me vividly was that, in defending this old view, Burke demonstrated that it was a far more effective guarantee of the liberties of the individual than the new idea, which was founded in the promise of those very liberties, only abstractly, universally, and therefore unreally defined. Real freedom, concrete freedom, the freedom that can actually be defined, claimed, and granted, was not the opposite of obedience but its other side. The abstract, unreal freedom of the liberal intellect was really nothing more than childish disobedience, amplified into anarchy.

In effect Burke was upholding the old view of man in society, as subject of a sovereign, against the new view of him, as citizen of a state. And what struck me vividly was that, in defending this old view, Burke demonstrated that it was a far more effective guarantee of the liberties of the individual than the new idea, which was founded in the promise of those very liberties, only abstractly, universally, and therefore unreally defined. Real freedom, concrete freedom, the freedom that can actually be defined, claimed, and granted, was not the opposite of obedience but its other side. The abstract, unreal freedom of the liberal intellect was really nothing more than childish disobedience, amplified into anarchy.

{...]

Good modernism is a constantly evolving tradition

I had been struck by Eliot’s essay entitled “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” in which tradition is represented as a constantly evolving, yet continuous thing, which is remade with every addition to it, and which adapts the past to the present and the present to the past. This conception, which seemed to make sense of Eliot’s kind of modernism (a modernism that is the polar opposite of that which has prevailed in architecture), also rescued the study of the past, and made my own love of the classics in art, literature, and music into a valid part of my psyche as a modern human being.

{...}

To break from your roots is to risk Hell

It was not until much later, after my first visit to communist Europe, that I came to understand and sympathize with the negative energy in Burke. I had grasped the positive thesis—the defense of prejudice, tradition, and heredity, and of a politics of trusteeship in which the past and the future had equal weight to the present—but I had not grasped the deep negative thesis, the glimpse into Hell, contained in his vision of the Revolution. As I said, I shared the liberal humanist view of the French Revolution, and knew nothing of the facts that decisively refuted that view and which vindicated the argument of Burke’s astonishingly prescient essay. My encounter with Communism entirely rectified this.

{...}

The best human beings can hope for

Briefly, I spent the next ten years in daily meditation on Communism, on the myths of equality and fraternity that underlay its oppressive routines, just as they had underlain the routines of the French Revolution. And I came to see that Burke’s account of the Revolution was not merely a piece of contemporary history. It was like Milton’s account of Paradise Lost—an exploration of a region of the human psyche: a region that lies always ready to be visited, but from which return is by way of a miracle, to a world whose beauty is thereafter tainted by the memories of Hell. To put it very simply, I had been granted a vision of Satan and his work—the very same vision that had shaken Burke to the depths of his being. And I at last recognized the positive aspect of Burke’s philosophy as a response to that vision, as a description of the best that human beings can hope for, and as the sole and sufficient vindication of our life on earth.

Conservatism as a lasting vision of human society

Henceforth I understood conservatism not as a political credo only, but as a lasting vision of human society, one whose truth would always be hard to perceive, harder still to communicate, and hardest of all to act upon. And especially hard is it now, when religious sentiments follow the whims of fashion, when the global economy throws our local loyalties into disarray, and when materialism and luxury deflect the spirit from the proper business of living. But I do not despair, since experience has taught me that men and women can flee from the truth only for so long, that they will always, in the end, be reminded of the permanent values, and that the dreams of liberty, equality, and fraternity will excite them only in the short-term.

The task before us

As to the task of transcribing, into the practice and process of modern politics, the philosophy that Burke made plain to the world, this is perhaps the greatest task that we now confront. I do not despair of it; but the task cannot be described or embraced by a slogan. It requires not a collective change of mind but a collective change of heart.

Hat tip to "Kipling" (Publius) at the Gods of the Copybook Headings

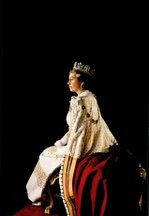

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

1 comments:

Looks very interesting. I must print this off to have a good read of it.

Post a Comment