"Not this tide"

“Have you news of my boy Jack?" Not this tide. “When d’you think that he’ll come back?” Not with this wind blowing, and this tide. “Has any one else had word of him?” Not this tide. For what is sunk will hardly swim, Not with this wind blowing, and this tide. “Oh, dear, what comfort can I find?” None this tide, Nor any tide, Except he did not shame his kind— Not even with that wind blowing, and that tide. Then hold your head up all the more, This tide, And every tide; Because he was the son you bore, And gave to that wind blowing and that tide! The ruined face of David Haig remains with you long after the end of My Boy Jack, a dramatization of the death of John Kipling, his famous father's only son, now playing on TVO. Haig's Kipling is not the bellicose bigot of legend, but a courteous, gentle, even sometimes prim story teller and father. Children flock to hear him, and he always greets them warmly. He adores his son Jack, with an overbearing zeal that easily overshadows Daniel Radcliffe's (Harry Potter himself) smaller figure. The British patriot par excellent, he warns of the dangers of German military aggression in the years before 1914, bemoaning, in a strident speech near the film's beginning, Britain's small profession force and the Kaiser's million man army. Haig conjures up Kipling the orator, powerful and stark in his projections; rape and murder to follow in the Huns' wake. In the film's opening scene Kipling is asked by George V, on behalf of the then Liberal government, to tone down his anti-German rhetoric. Kipling politely refuses and the King is delighted. The relationship between Kipling and his sovereign is more than an illustration that the poet lived up to one of his most famous lines - "walk with kings -- nor lose the common touch" - but also a parallel between two fathers. The King's youngest son, Prince John, was a sickly child who died at 14 from "seizures."

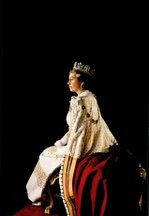

The ruined face of David Haig remains with you long after the end of My Boy Jack, a dramatization of the death of John Kipling, his famous father's only son, now playing on TVO. Haig's Kipling is not the bellicose bigot of legend, but a courteous, gentle, even sometimes prim story teller and father. Children flock to hear him, and he always greets them warmly. He adores his son Jack, with an overbearing zeal that easily overshadows Daniel Radcliffe's (Harry Potter himself) smaller figure. The British patriot par excellent, he warns of the dangers of German military aggression in the years before 1914, bemoaning, in a strident speech near the film's beginning, Britain's small profession force and the Kaiser's million man army. Haig conjures up Kipling the orator, powerful and stark in his projections; rape and murder to follow in the Huns' wake. In the film's opening scene Kipling is asked by George V, on behalf of the then Liberal government, to tone down his anti-German rhetoric. Kipling politely refuses and the King is delighted. The relationship between Kipling and his sovereign is more than an illustration that the poet lived up to one of his most famous lines - "walk with kings -- nor lose the common touch" - but also a parallel between two fathers. The King's youngest son, Prince John, was a sickly child who died at 14 from "seizures."

The two men's pride and grief book-end the film and the 1997 play, both written by David Haig, who bears an uncanny resemblance to Kipling. The moral center of the play rests not Kipling's grief but his perceived guilt. The great poet is keen to see English manhood do its duty against the German menace, even his short-sighted, seventeen year old son. The boy's mother, played with matronly grace by the very unlikely Kim Cattrall, and sister are horrified at the prospect of young Jack in combat, both, at different points in the drama even call Kipling a murderer. The composed and courteous Haig / Kipling unhinges himself only twice in the film, when he receives the fateful telegram, and when the word murderer at last flies from his wife across the Tudor great room of Bateman's, the family's home. "I've considered the possibility" is his angry and weeping response. The film condenses time considerably, the Kiplings are shown frantically searching for their son, declared MIA at the Battle of Loos in 1915. They exhaustedly review photographs of captured Tommies from the Red Cross, Cattrall's Caroline snapping that her husband's influence had gotten the unfit boy into the army, his influence would find him now. Closure is given in the film, at least, to the Kiplings in the form of an inarticulate private's sobbing description of their son's last moments. Popular with his men, Lieutenant Kipling dies before a machine gun position, Radcliffe's flinching and contortions, as the bullets strike him, is interspersed with the private's story.

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

3 comments:

This was an incredible film. Superbly written and acted. A candid, sympathetic survey of British values and culture.

Matt

"Kipling" I must say is a very capable reviewer of film. He makes me want to go and watch it, and watch it I will.

The actor who played the King was awful though. Strange, because he's been a fairly run-of-the-mill good actor in other things, but the bit at the end of "My Boy Jack" was just completely unbelievable; he was no King!

Post a Comment