H.M.S. Hood: "the beauty, grace and immaculate strength of her"

We note, belatedly, the death of Albert Edward Pryke "Ted" Briggs MBE, the last living survivor of the sinking of HMS Hood. Destroyed in tracking the Bismarck in May 1941, the Hood was the pride of the Royal Navy. Of its 1,418 crew only three survived. The story of signalman Briggs and the Hood, retold in countless books, films and TV documentaries, is also a love story. It was the chance sighting of HMS Hood, anchored off the river Tees at the age of 12, that charged the young lad with the idea of life at sea. Briggs later recalled "I stood on the beach for some considerable time, drinking in the beauty, grace and immaculate strength of her." As with generations of young boys before him, Briggs went to his local recruiting office, being told to come back when he was 15. A week after his 15th birthday he returned and was accepted. On June 29 1939 he joined HMS Hood's crew. "It never once occurred to me that she might be sunk," he said. "As far as I was concerned, she was invincible. And everybody on board shared this view."

We note, belatedly, the death of Albert Edward Pryke "Ted" Briggs MBE, the last living survivor of the sinking of HMS Hood. Destroyed in tracking the Bismarck in May 1941, the Hood was the pride of the Royal Navy. Of its 1,418 crew only three survived. The story of signalman Briggs and the Hood, retold in countless books, films and TV documentaries, is also a love story. It was the chance sighting of HMS Hood, anchored off the river Tees at the age of 12, that charged the young lad with the idea of life at sea. Briggs later recalled "I stood on the beach for some considerable time, drinking in the beauty, grace and immaculate strength of her." As with generations of young boys before him, Briggs went to his local recruiting office, being told to come back when he was 15. A week after his 15th birthday he returned and was accepted. On June 29 1939 he joined HMS Hood's crew. "It never once occurred to me that she might be sunk," he said. "As far as I was concerned, she was invincible. And everybody on board shared this view."

Few in the Admiralty, and fewer among the officers and ratings, understood how air power had forever changed the nature of naval warfare. Visionaries, like the American General Billy Mitchell and Japan's Isoroku Yamamoto, had foretold the death of the great battleships. Hood was not, like her sister ship Prince Wales, destroyed by air assault. Instead, in one of naval history's luckiest shots, the Bismarck succeed in landing a shell precisely on the Hood's magazine, sinking the ship in minutes. For years complaints had been made about the thinness of Hood's deck armour, yet few would have imagine so specularly successful a shot in battle conditions. Through out the inter war years, Hood was launched in 1918, spent much of her time on goodwill visits. These were the years of the Treaty of Washington, a face saving deal between Britain, the United States and the other major naval powers. While nominally an arms limitation agreement, in truth it allowed the penny-pinching US Congress to cut back on naval spending, and allowed the Royal Navy the illusion of genuine parity with the Americans. Washington limited the size of both the USN and RN to parity in numbers and strength, a much needed relief for the strained post war Treasury. Finance would weaken the Royal Navy and her grand ships, but technology would make them museum pieces. The aircraft carrier, a British invention, transformed much of the world's great navies into seaborne aerial platforms. Yet there is still no shortage of boys like Ted Briggs, who dream of ships of immaculate beauty.

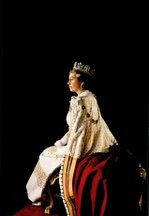

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

6 comments:

This post touches Beaverbrook's heart. I believe there is still one living survivor of the Battle of Jutland, incredibly enough.

Do you know what I think that's a shame? England did not conserved one single battleship just like the US and japan did. The UK had such a quantity of historical ships, like the Iron Duke, the Queen Elizabeth class, the R class or even the King George V class. All sent to scrap! What a scandal...

Not quite. From wikipedia:

"HMS Caroline is a C-class light cruiser of the British Royal Navy (RN). Caroline was launched and commissioned in 1914, making her the second-oldest ship in RN service, after HMS Victory. She acts as a static headquarters and training ship for the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR), based in Alexandra Dock, Belfast, Northern Ireland. She is the last remaining British World War I light cruiser in service, and the last survivor of the Battle of Jutland still afloat."

Personally I think the HMS Victory makes up for the negligent failure to preserve a few relatively recent battleships, however historical. Having said that, it would have been nice to stroll around on the Iron Duke and whatnot.

I'm of two minds about the Washington Treaty. On the one hand, the treaty prevented some beautiful ships from being built, especially by the US (e.g. the first South Dakota class battleships [not the 1930's class of the same name]), but also by Britain, that certainly would have come in useful later.

On the other hand, and as pointed out here, the US Congress was in a penny-pinching frame of mind, and the British were just strapped. It is probable that the ships would not have been built anyway. However, the Japanese WOULD have built additional ships, although their financial circumstances were strained also, they did not have the political constraints operating on them that the US, Britain and France did. On balance, I'd say the Washington Treaty was a good thing for the US/UK and France.

I would argue that the second of these naval treaties -- the London Treaty of 1930, was pernicious. It extended the prohibitions of the Washington Treaty, but Germany, Italy and Japan were now more interested in building. . .and the London Treaty contained restrictions on the size of battleships which certainly adversely affected US and British building programs of the 30's -- e.g. the almost scandalous 10x14" gun configuration of the King George V class ships (rather than 12X14" or 9x16" inch).

The Germans and the Japanese completely disregarded the tonnage restrictions of this treaty, the US, UK, French and Italians disregarded them too, but not as blatantly.

It was unfortunate that the Treaty stripped Australia of its one battleship, in my opinion. Had we not effectively been stripped of our navy we may have felt more inclined to maintain a stronger navy in the leaad up to WWII which may have deterred the Japanese somewhat. Or it may not have, this is pure speculation of course.

I once heard an historian say that while there were negative aspects of the Treaty, it probably prevented the Anglo-American War of 1924.

Post a Comment