Why Monarchy? Why Tradition?

I am sometimes reproached for my support of the monarchy. The standard line, little challenged by the small band of valiant Canadian monarchists, is that the monarchy is an anachronism, or useless, or expensive or undemocratic or foreign or about half a dozen other reasons, usually thrown out in no particular order. What does seem to unite the anti-monarchists - at least in Canada there is no significant movement in favour of a republic - is an emotional repugnancy toward the monarchy which grabs at whatever it can find to remove the crown from Canada. The emotion is by no means strong, really more of a nuisance they want to get rid of. I've met very few ardent republicans / anti-monarchists, it's simply not a grand enough cause to attract much attention either way. The small band of monarchists, unfortunately, often chooses equally questionable ground to defend the crown against its enemies.

I am sometimes reproached for my support of the monarchy. The standard line, little challenged by the small band of valiant Canadian monarchists, is that the monarchy is an anachronism, or useless, or expensive or undemocratic or foreign or about half a dozen other reasons, usually thrown out in no particular order. What does seem to unite the anti-monarchists - at least in Canada there is no significant movement in favour of a republic - is an emotional repugnancy toward the monarchy which grabs at whatever it can find to remove the crown from Canada. The emotion is by no means strong, really more of a nuisance they want to get rid of. I've met very few ardent republicans / anti-monarchists, it's simply not a grand enough cause to attract much attention either way. The small band of monarchists, unfortunately, often chooses equally questionable ground to defend the crown against its enemies.

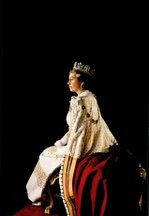

The word most often used to uphold the monarchy is tradition. This in and of itself is the best argument that can be offered for the continuance of monarchical institutions in Canada. Without a resort to tradition there is simply no explaining allegiance to an eighty year old woman who, until her accession to the throne, demonstrated no particular qualifications for the position ahead of millions of other young men and women at the time. There is certainly no understanding why Canada, a sovereign nation and one of the world's leading developed nations should have as its head of state the hereditary monarchy of another country some three thousand miles away. Tradition, Canadian tradition in particular, should be the crux of the Canadian monarchists defense of the crown. What St. Paul said about the resurrection, that if it never happened he was preaching in vain, applies to the monarchy and tradition. If the monarchy were not part of Canadian history then there would be no point in having a Canadian monarchy.

Where most monarchists err is in their understanding of tradition, a vital mistake made by many conservatives as well. Tradition is cloaked in a hazy mist of warm emotions, it lacks height, width or depth. This is when the word is understood broadly, sometimes it is also seen strictly as narrow ritual, action repeated for the sake of continuity and nothing else. Others have done this before me and I carry on feeling comfort in the fellowship of those before and, one assumes, those after me. If this is all tradition can and should mean then neither it or the monarchy, to take the current case in point, can long last except as a refuge or hobby horse.

Since the Enlightenment monarchy and tradition have both suffered from two powerful intellectual forces born, or perhaps more accurately reborn and refined, in the eighteenth century; democracy and reason. The two are not necessarily complimentary forces in history or intellectual discourse. The rule of the majority and the principles of induction and deduction often have only a nodding acquaintanceship. There link with one another in the modern world has been from that other great force of the enlightenment, liberty. Liberty does not necessarily require democracy. However one understands liberty the means to maintain it are open to question. The Athenian democracy famously failed to uphold anything that might, either in modern or ancient terms, be called liberty. Britain's constitutional monarchy upheld a degree of liberty, as most English speaking moderns broadly understand it, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries unprecedented in human history, yet less than one percent of the adult population could vote.

What system of government might best uphold liberty was the great question confronting Western political thinkers in the decades after the French Revolution. The conclusion reached, at least in the English speaking nations, was that a democracy with constitutional limitations, particularly as regards to individual rights and executive, legislative and judicial procedures, would best guarantee liberty. Without some kind of check on the power of the executive, monarchical or otherwise, tyranny was all too possible. Some kind of electoral check on the power of the executive, as expressed by the legislative branches of government could, in conjunction with checks on both branches by the judiciary, with reference to a written or unwritten constitution. The wider the franchise, it was felt, the better the check on the executive. Democracy, unlike in Athens, could uphold liberty if properly controlled. Matched with this was the more pragmatic concern about how to control a rapidly urbanizing population, Until the advent of totalitarian government in the 20th century, and all its tools of control, only some kind of democracy seemed able to achieve social stability in the 19th, if only as a peaceful outlet of discontent.

The linking of democracy with liberty was sanctified, if one will admit the abuse of the language, by reason. Liberty was, until the 20th century at least, derived to some extent from natural law arguments. These were not necessarily atheistical. They might exemplify a Newtonian / Lockean approach; divine conception but rational functioning. One big miracle and all that followed may be derived empirically. Reason explained where liberty came from and why it was important. Reason could argue that democracy worked to sustained liberty, if the nature of both were understood and reason applied in the establishment and maintenance of governments.

Tradition and monarchy have little place in this narrative. Reason asks why certain traditions exist and demands rational explanations for their continuance. Appeals to ritual continuity or divine sanction will go nowhere with the rationally minded. Appeals to faith, trying to uphold both monarchy and tradition are equally doomed on these terms. One can try to revolt against reason and liberty but on what grounds? The material and spiritual well-being that brought about the scientific, industrial and liberal revolutions of the 18th and 19th century was unprecedented. Could one really turn one's back on all that? With nothing more than a hazy appeal to tradition and faith?

Monarchy maintained itself in Britain, and what became the Commonwealth, because it became an instrument of liberty. In much of the world monarchy obstructed both democracy and liberty; in Britain it ensured that liberty was preserved as genuine mass democracy emerged. Given that only a handful of nations achieved this feat, and only one, the United States, was a republic, this might at first have helped the image of the monarchy as co-defender of liberty with limited democracy. Instead as time past the monarchy, which might be praised for its role in ushering in liberal democracy, was now seen as dispensable. Its services rendered to the people, the people were all grown up and could do without. Don't let the palace gates hit you on the way out.

Monarchists cannot, as they could a century ago, argue that freedom requires a monarchy to hold back the worst excesses of oligarchy or democracy. If even the French can run a republican liberal democracy then why would the English, and their commonwealth descendants, need a monarchy? Tradition was the last argument left and it was now in the public understanding as much an anachronism as monarchy itself, a process made worse by the crippling historical amnesia imposed by modern public education on the general populace. The nations of the English speaking world do not know their past or seem to aspire to anything not of the moment. If a society abhorrent of tradition has little time for the past, a society proudly ignorant of the past is far worse.

The neo-barbarians aside, tradition is necessary, but it must be tradition on rational grounds. This seems like a contradiction in terms. Tradition is historical and the historical is often accidental, not rational. An even superficial examination of the British constitution almost beggars belief. A feudal political superstructure that has over the centuries been rigged - a more polite term might be improvised - to accommodate mercantilism, laissez-faire classical liberalism, the welfare state, full blown democratic socialism and now some kind of Thatcherite-Blairite mixed economy. Only God, or whatever, knows what Gordon Brown has in store for Merry England's queer looking ship of state in the years ahead. Yet it works. Yes, the Minister of Finance is called by the absurd title of Chancellor of the Exchequer, which was originally a relatively minor office responsible for accounting procedures. The very name "exchequer" refers to a "checkered" board used by medieval officials to count tax receipts.

There is an office in the British cabinet called the Lord Privy Seal - who is, as the very old joke frequently attributed to Ted Heath goes, neither a Lord nor a Privy nor a Seal; another member of the current cabinet holds the title of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and another is called Lord President of the Council, which perplexes Americans to no end. "How can someone be a Lord and a President and what Council are you talking about?" When they are told that the Lord President is a mid-ranking member of the Cabinet you might as well end the conversation there. Explaining how the office of Prime Minister has been in existence since about 1721, yet there was no mention of the word Prime Minister on any legal documents until 1905, and that even today the powers of the office are determined more by convention than anything written down in black and white, is simply inexplicable to most.

It all works because the men and women who operate and support the British constitution accept certain core values, values which themselves have been evolved, or discovered, through trial and error guided by certain theoretical principles, which in their turn have also evolved and changed over time. What makes the British constitution work in the form it is in today is tradition. The judges wearing whigs and black robes, allusions to medieval origins of the participant's roles and the common law itself, or the bizarre custom of referring to the Speaker or Lord Chancellor when responding to another parliamentarian's questions, are all tangible symbols of tradition. They are all, however, accidental products of history. One could do away with the form and the substance would probably remain of what was being said or decided. A house stripped of ornamentation or styling is no less structurally sound.

Tradition in form or procedure is akin to ornamentation. Traditional values, beliefs or attitudes are something else. That a belief, a value or an attitude is traditional, i.e historical, gives it no inherent normative value. Most societies have their own conservatives denouncing the evils of modernizers or "liberals" and decrying the decline of "traditional values." With the exception of Anglo-Saxon based societies these conservatives are typically little more than primitive tribalists and medievalists in spirit, decrying the march of individual liberty, the rule of law, rational discourse and liberal democracy. Our conservatives are generally better because the values they are trying to conserve are better. No one, however, is seriously arguing in the debate over the monarchy that Her Majesty be given real decision making power. The debate over the monarchy is a debate over symbols and not directly values. This may seem an odd distinction - aren't symbols meaningless without values? - but in our current cultural climate a separate argument must first be made for the importance of symbols, a necessity unimaginable only two generations ago. A symbol is a concretization. Every human being, even the most depraved of the moderns, needs something tangible, something to point to and say to themselves and others: "This is what I believe," or "this is what I am." The thing being symbolized, and it must be a thing, an abstract thought does not serve the same function, itself has little intrinsic value or meaning. A flag is a piece of cloth, a crown a golden trinket, we imbued these things with meaning because we need the hard fact before us. The thing itself is almost incidental, it needs to be a thing but what kind is open. We could idolize a rock, many cultures have, but few sophisticated cultures choose to do so. It helps if the symbol chosen tells a story. The symbolic is traditional and the traditional is often accidental, but that does not make either random. It is accidental that you met your wife at Union Station on a Tuesday afternoon as you both reached for a Snickers bar. Your choice of this particular women as your wife is not accidental. The American flag has thirteen strips, alternating red and white, overlain with a blue canton holding fifty white stars in its top left hand corner. Each of those elements has a historical origin. The fact that there are thirteen stripes is purely accidental. Had Benedict Arnold succeeded in his 1775-1776 expeditions to Quebec he might have gone down in history as a hero, and the American flag would have contained fourteen stripes. The detail is accidental, the meaning is anything but. Neither are the emotions.

A symbol is a concretization. Every human being, even the most depraved of the moderns, needs something tangible, something to point to and say to themselves and others: "This is what I believe," or "this is what I am." The thing being symbolized, and it must be a thing, an abstract thought does not serve the same function, itself has little intrinsic value or meaning. A flag is a piece of cloth, a crown a golden trinket, we imbued these things with meaning because we need the hard fact before us. The thing itself is almost incidental, it needs to be a thing but what kind is open. We could idolize a rock, many cultures have, but few sophisticated cultures choose to do so. It helps if the symbol chosen tells a story. The symbolic is traditional and the traditional is often accidental, but that does not make either random. It is accidental that you met your wife at Union Station on a Tuesday afternoon as you both reached for a Snickers bar. Your choice of this particular women as your wife is not accidental. The American flag has thirteen strips, alternating red and white, overlain with a blue canton holding fifty white stars in its top left hand corner. Each of those elements has a historical origin. The fact that there are thirteen stripes is purely accidental. Had Benedict Arnold succeeded in his 1775-1776 expeditions to Quebec he might have gone down in history as a hero, and the American flag would have contained fourteen stripes. The detail is accidental, the meaning is anything but. Neither are the emotions.

The need to have symbols relates to man's nature - yes we do have a nature - as emotional beings. As The Monarchist recently pointed out:

Republics are bloodless abstractions. We all know this. We all know they are founded upon conceptual notions such as equality, fraternity and liberty, rather than the more tangible drivers that are the soul of monarchies, like human connection, continuity and experience.

This is rather too harsh. The American Republic was founded on a conceptual notion, which in its first principles was as radical then as now, yet it too acquired traditions and symbols that were not bloodless. For America to become a monarchy would be as much a betrayal of her traditions and her symbols as if we abandoned our monarchy. The common thread is the emotional link with the symbols and the traditions. The great dichotomy of Western thought, the supposed conflict between mind and body, between reason and emotions, has lead many monarchists into the trap that monarchy cannot be defended on rational grounds. Monarchy is traditional and emotional, something hazy, as I described at the beginning of this piece, something soft that is disintegrating in the hardness of the modern world. Yet emotions are not necessarily irrational, they can and should be integrative.

An emotion, as Ayn Rand among others identified, is a sum of thoughts, beliefs and experiences. An emotion tells you something about yourself, about your current situation that it might take hours or years to describe abstractly in words. Emotions are not necessarily antagonistic to reason they should be complimentary, This does not mean we can substitute emotions for reason. If the intellectual history of emotions, how they are perceived by individuals and society, was in the nineteenth century all about repression, since the 1960s it has been all about "liberation." In truth the "liberation" was little more than replacing a weakening repression with near total anarchy. If feels right do it, damn the facts, the precise observe of the previous attitude which was damn your emotions look at the facts, or social convention. Emotions are also facts, not existential ones, but they are real none the less and are providing you information.

In either case there was only fitful attempts to integrate reason with emotion, to understand why and how rather than to pretend. The repression of the past and the anarchy of the present are both forms of pretense, albeit the later allowed for some measure of social cohesion. A better understanding of emotions will help us have a better understanding of tradition, that tradition can be both emotional and rational, that symbols can be both rational and emotional and that allegiance to the crown can be both rational and emotional.

The crown is a living symbol of Canada's peaceful constitutional development. We do not settle our political disputes by violence, we do so through argument in public debate. The mob does not rule in Canada, neither do a few men in dark corners. We are a free nation and the way be became a free nation was by the route of constitutional monarchy. Other nations have other traditions. They are not necessarily better or worse, again, tradition is not normative outside of a philosophical and historical context. Each family has its heirlooms that are usually worthless to outsiders. These trinkets have their history and their emotional context.

An individual's symbol reinforces his or her individuality, a family symbol their unity, a national symbol its unity. In Canada, unlike in America, or France, or Germany or Portugal, freedom wears a crown. Certainly the history of the crown in Britain is complex and occasionally bloody. I would have fought with Cromwell at Naseby, have been steadfast with Shaftesbury during the Exclusion Crisis and cheered the Seven Immortals as they went off to summon William of Orange onto the throne and into British history and tradition. We stand at the endpoint, so far, of a tradition. Its sum makes the Crown a symbol of liberty today. The American colonists too viewed the monarchy as a symbol of liberty, until the monarch of the day, and his government, betrayed them. Our history tells a different story and we derived a different tradition. In that spirit, with wholeness of heart and mind, let me say:

Vivat Regina!

Originally Posted at The Gods of the Copybook Headings

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

3 comments:

Thank you for reposting this, Kipling. I'm going to save it under Treasured Posts.

I see so much talk from the republican side in the media and in the public, and so few for the crown, I had even begun to doubt myself, and why i felt so loyal to it, as oppose to the "country" they seem to sprout but what I never seem to see the advantages of.

I thank you for restoring my faith, given me a sword to fight back, where before i had alway been on the defensive

thank you. God Save the Queen.

No one, however, is seriously arguing in the debate over the monarchy that Her Majesty be given real decision making power.

I, for one, would certainly argue for this, at least as far as judicial matters are concerned. At least, make the Monarch the final court of appeal above the Supreme Court. The title of "Lord/Lady High Justice of the Realm", along with some real decision-making power, would be a good thing in my perspective.

For it is wrong that the Monarchy - currently Windsor rather than Stuart - has been reduced to figure head status. That makes England and the Commonwealth nothing better than "crowned republics". And that is just dead wrong.

Post a Comment