How Lord Mountbatten Saved India

By Ramachandra Guha, The Spectator In the fawning books that have been written about Louis, Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, the man is typically portrayed as a wise umpire, successfully mediating between squabbling schoolboys: whether India and Pakistan, the Congress and the Muslim League or Mahatma Gandhi and M.A. Jinnah.

In the fawning books that have been written about Louis, Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, the man is typically portrayed as a wise umpire, successfully mediating between squabbling schoolboys: whether India and Pakistan, the Congress and the Muslim League or Mahatma Gandhi and M.A. Jinnah.

Curiously, however, Mountbatten's real contribution to India and Indians has been rather underplayed by his hagiographers. This was his part in solving a geopolitical problem the like of which no newly independent state had ever faced. For when the British departed the subcontinent, they left behind more than 500 distinct pieces of territory. Two of these were the newly created nations of India and Pakistan; the others, the assorted chiefdoms and states that made up what was known as "Princely India."

There were so many princely states that there was even disagreement as to how many. One historian puts their number at 521, another at 565. At one end of the scale were the massive states of Kashmir and Hyderabad, each the size of a large European country; at the other end, tiny feudal fiefdoms of a dozen or fewer villages.

By the mid-1940s, these chiefdoms found themselves facing a common problem: their future in a free India. In the first part of 1946 British India had a definitive series of elections; but these left untouched the princely states. On June 3, 1947, both the date of the final British withdrawal and the creation of two Dominions was announced -- but this statement also did not make clear the position of the states. Some rulers now began, in the words of the political scientist W.H. Morris-Jones, "to luxuriate in wild dreams of independent power in an India of many partitions."

The work of bringing the Princes into line was the responsibility of the Indian home minister, Vallabhbhai Patel, and the energetic secretary to the Ministry of States, V.P. Menon. Between them they worked on a draft Instrument of Accession, whereby the Princes would agree to transfer, to the new Indian government, control of defence, foreign affairs and communications. On July 5, 1947, Patel issued a statement appealing to the princes to accede to the Indian Union on these three subjects. As he put it, the alternative was "anarchy and chaos."

Four days later Patel and Nehru met the Viceroy and asked him "what he was going to do to help India in connection with her most pressing problem -- relations with the [Princely] States." Mountbatten agreed to make this matter "his primary consideration." Later that same day Gandhi came to meet Mountbatten. As the Viceroy recorded, the Mahatma "asked me to do everything in my power to ensure that the British did not leave a legacy of Balkanisation."

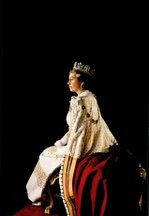

Mountbatten was being urged by the Indian leaders to go out and bat for them against the states. This he did most effectively, notably in a speech to the Chamber of Princes delivered on July 25, for which the Viceroy had decked out in all his finery, rows of military medals pinned upon his chest.

The Indian Independence Act, said Mountbatten to the princes, had released "the States from all their obligations to the Crown." He advised them therefore to forge relations with the new nation closest to them, and sign the Instrument of Accession.

Mountbatten's talk to the Chamber of Princes was a tour de force. It finally persuaded the princes that the British would no longer protect or patronize them, and that independence was a mirage. And this word was carried not by a rabble-rousing Indian nationalist but by the representative of the King-Emperor, who was a highly decorated military man, and of royal blood besides.

By Aug. 15, virtually all the states had signed the Instrument of Accession. Meanwhile the British had departed, never to return. Now the Indians went back on the undertaking that if the princes signed up on the three specified subjects, "in other matters we would scrupulously respect their autonomous existence." In state after state, nationalist organizations demanded "full democratic government." In some states, protesters took possession of government offices, courts and prisons.

The Indian government cleverly used the threat of popular protest to make the princes fall in line. They had already acceded; now they were being forced to integrate, that is, to dissolve their states as independent entities and merge with the new nation. By 1950, the 500 states had disappeared from the map. All the Maharajas were left with were their titles, their palaces, their jewels and an annual allowance provided them by the government of India.

Vice-Regal Saint:

Vice-Regal Saint:

.gif)

.gif)

1 comments:

How ironic that this was the man who oversaw British troops leaving India who the IRA murdered, a man deeply sympathetic to the national asperations of the Irish, the one man in the establishment who could have been seen as such.

It served absolutely no purpose but instead sent a wave of revulsion against the terrorists.

As an aside, I remember reading Christopher Hitchens's article that said how "The consulate in Chicago is still reeling from the time when [Princess Margaret] commented on the assassination by saying bluntly: 'Irish pigs.' Nobody quite believed the cover story that this was a misquotation for 'Irish jigs.' Ah, the magic of monarchy..."

Post a Comment